450 BCE

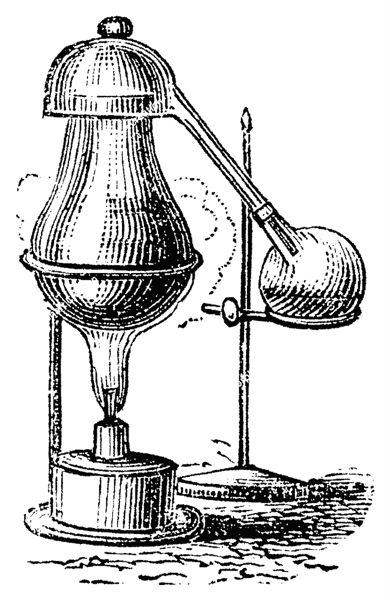

Alembic Pot Still

While there is little doubt as to the role played by Al-Jabir in bringing distillation into modern world, an irrefutably accurate alembic pot still design was recently discovered in a museum in Pakistan. Dated at around 450 BCE, this terracotta still was discovered on the Indian sub-continent in the ancient city of Taxila, the old capital if the eastern Punjab region, 30km northwest of modern-day Islamabad.

70 AD

Medicinal Juniper

Gin’s core ingredient, juniper, has been combined with alcohol as far back as 70 A.D. At that time, a physician named Pedanius Dioscorides published a five-volume encyclopedia about herbal medicine. Within these papers is a detailed description of the use of juniper berries steeped in wine to combat chest ailments.

790 AD

Father of the Pot Still

Abu Musa Jābir ibn Hayyān – known simply as Gerber or Al-Jabir by the scholarly Latin communities – is acknowledged as being the first documented to design and implement the common “pot still” circa 790 AD. Today the pot still remains an essential tool for producing premium spirits and other chemical compounds.

Abu Musa Jabir Ibn Hayyan Al-Azdi, sometimes called al-Harrani and al-Sufi, is considered the father of Arab chemistry and one of the founders of modern pharmacy. He was known to the Europeans as Geber. He was born in the city of Tus in the province of Khorasan in Iran in 721 AD.

1500's

Gin is born

In the 16th Century, the Dutch created a medicinal alcohol using Juniper as the main ingredient. The name “Genever” derives from the Latin for juniper. This medicine was given to troops as part of their daily rations.

During the 17th century, Dutch troops fought alongside the English to ward off the attack of Louis XIV. The Dutch troops drank Genever heavily before going into battle and were deemed to be excessively brave. The English troops then decided to also drink Genever before going into battle and noted they had imbibed the Dutch’s courage hence the term “Dutch Courage”.

During the time of the war, English troops would take their Genever rations home with them and share it amongst their peers. The juniper flavoured spirit soon became vastly popular, especially with the poor. This was because just a few sips of water could kill you and the only other available drink was the vastly overpriced beer. The name ‘Genever’ was too much of a mouthful for some and was eventually shorted to ‘Gin’.

1689

Mother's Ruin

In 1689, King William III of Orange overthrew James II of England and became the King of England. The following year saw King William pass an act known as the ‘Distillers Act’, subsequently allowing the public to produce alcohol for free in their own home providing they passed a 10-day public notice, the law also restricted the importation of Brandy and wine.

This new law coupled with the taste for juniper flavoured spirits meant that pretty much anyone and everyone started producing juniper flavoured spirits. Unlike the Dutch, these spirits were not made using high quality grains to produce the spirit, they used low quality grain cut with mentholated spirits and turpentine which was then flavoured with locally grown juniper berries, anything else that was grown locally and natural sweeteners like liquorish root and rose water to mask the horrible flavours and make the gin more palatable. This was the start of a period that was known as the ‘Gin Craze’.

In 1720, the mutiny act was passed which stated that anyone who was distilling alcohol wouldn’t have to house soldiers in their home. These factors massively encouraged local gin production, so much so that in 1730 the number of gin shops in London exceeded 7000 which was one in every three public houses. By 1733, the average person was drinking 14 gallons of gin per annum, approx. 1.3 litres of gin per week. 1 in 3 structures in London produced or sold gin. At approximately 160 proof, this gin was highly intoxicating, not only was it strong but it wasn’t being sipped like a gin and tonic, in some cases it was being drank in vast quantities some were drinking around half a litre per day.

The gin obsession was blamed for misery, rising crime, madness, higher death rates and falling birth rates. Gin joints allowed women to drink alongside men for the first time and it is thought this led many women neglecting their children and turning to prostitution, hence gin becoming known as ‘Mother’s ruin’.

1717

A Sloe beginning

The history of sloe gin in the UK is, in many ways, linked with the history of land enclosure. Beginning as early as the 17th century, Parliament passed a series of Enclosure Acts that transformed common land into individual farmsteads and properties. In order to break up the land, hedgerows were needed…and, thanks to its dense, spiny branches, the blackthorn was used throughout Britain as a kind of natural fencing. (Today’s foragers know that hedgerows are still some of the very best places to go sloe-harvesting.)

A side effect of all those hedgerows was new, bumper crops of sloe berries. Though sloes on their own are notoriously tart and astringent, it certainly seemed a waste to ignore the annual harvest…and those living in the country soon learned that the best way to take advantage of the berries was to steep them in alcohol.

However, the gin that was being made at that time wasn’t the best of quality, and its over-consumption famously sparked London’s Gin Crazed debauchery. A poem dating from 1717 singles out homemade sloe gin beverages for criticism as a social ill. While 19th-century accounts describe sloe gin being heedlessly gulped by Londoners as a sort of poor-man’s port.

For a long time, sloe gin didn’t enjoy the most elevated of reputations. But all that started to change in the late 19th century, when more established distilleries began to produce their own, higher-quality sloe gin.

1731

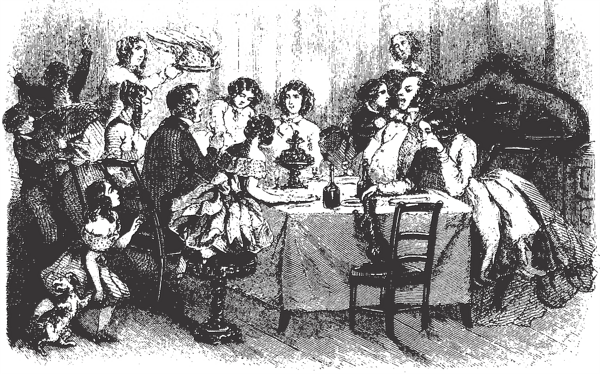

A drinking problem

The “gin and gingerbread” phenomenon began in 1731. Whenever the weather turned, crowds would gather to explore the stalls and tents selling hot gin and gingerbread that popped up along the frozen River Thames. Enterprising Londoners looked to make a quick shilling out of what became known as the London Frost Fairs. Sounds innocent enough...

...within five years, the government started to realize that society had a problem on its hands. The people of England began to either go totally insane or just die. Gin distillation was, again, a free-for-all, with things like turpentine, sulphuric acid, and sawdust going into the juice.

As a means of getting the country’s gin-obsessed drunkards to tone it down, a distiller’s license was introduced. The price tag was £50, an exorbitant cost at the time, and the industry plummeted. Only two official licenses were issued in the next seven years. The business of informing, however, boomed in tandem. Anyone with information on illegal gin operations was compensated £5.

1736

Old Tom

We all know London is the home of gin and has been for 300 years or so. The history of gin drinking is quite colourful, filled with rogues, strumpets and vagabonds who lurched from one tavern to another in search of the juniper juice once known as Geneva. Many Gin acts were passed during the 1700’s in an attempt to control the production of shall we say, inferior quality gin. Some of these acts were harsh and often caused uproar amongst the distillers and gin hawkers of Ye Olde London Town.

One such act was put into force at midnight on September 29th 1736. This act meant you had to buy a license to sell gin. The license fee was £50, which given many people didn’t earn that in a year was quite restrictive.

Old Tom plays a significant role in the history of gin. Quaffed by the bucket load during the 18th and 19th centuries, it served as something of a bridge between Dutch Genever and London Dry, drier than the former and sweeter than the latter.

Old Tom Gin emerged in an era of heavy drinking and primitive distilling. The column still hadn’t yet been invented, so spirits were harsh at the best of times. Keen to increase profit margins, the unscrupulous distillers of this era would add to this by cutting their spirits with turpentine and sulphuric acid, creating gins that were barely palatable and often deadly. Still, the English are a determined bunch when it comes to drinking and they turned to gin in their droves. In order to make it drinkable, distillers sweetened the juniper-laced spirit with liquorice or sugar, thus creating a whole new category of Gin.

There are many, many stories claiming to reveal the etymology behind the spirit. One such story commonly heard story points towards the biography of author Captain Dudley Bradstreet, who claims to have invented a one-stop gin shop known by history as a Puss & Mew shop. This would help enterprising booze hounds to get their fix following the Gin Act of 1736. In the window of a little building in London he hung a sign featuring an old tomcat. Beneath the cat’s paw there was a slot into which the city’s thirsty masses could drop a coin. Coin received, Bradstreet would pour a shot of gin through a lead pipe, directly into the patrons waiting mouth. That this happened is not in dispute, but whether it led to the name Old Tom is highly unlikely as Bradstreet makes no mention of the term in his autobiography.

1751

Gin Lane

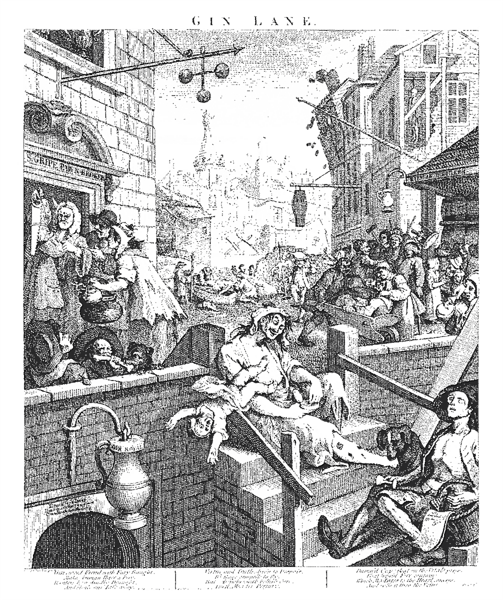

Things took a turn for the weirder in 1751, hallmarked by a series of very dark etchings by William Hogarth. “Beer Street,” depicted the relative safety of beer drinking in comparisoin to gin.

“Gin Lane,” on the other hand shows a rather depressing scene of people losing their literal minds to gin. In this image a gin-drunk mother drops her baby over the side of a staircase, an inebriated man beats himself over the head with some bellows while toting a baby impaled on a spike, a suicidal barber emcrusted with syphilis sores, and other charming moments.

These etchings came in response to stories like that of Judith Defour, a silk-thread spinner from Spitalfields. Defour was supposedly driven so utterly mad by her gin addiction that, in 1734, she took her 2-year-old daughter Mary to a field with a friend named Sukey. The two women removed all of the toddler’s clothes and abandoned her in a ditch. The pair then proceeded to sell the clothing for money to purchase a quartern of gin. Poor Mary died and her mother was promptly sentenced to death by hanging.

During the 18th century, gin was by and large the most heavily vilified spirit, It was blamed for the death of thousands by overconsumption, murder, negligence, and insanity, which incited measures to outlaw its production and consumption, but to little avail.

Then came the Gin Act 1751, a parliamentary measure intended to crack down on spirits consumption. It raised taxes and fees for retailers and made licenses more difficult to come by. In addition to beer, the consumption of tea was promoted as well.

“By 1830, beer became cheaper than gin for the first time in over a century, England became, for a few moments, a nation of beer drinkers once again.

1769

London Dry

Gordon's London Dry Gin was developed by Alexander Gordon, a Londoner of Scots descent. He opened a distillery in the Southwark area in 1769, later moving in 1786 to Clerkenwell. The Special London Dry Gin he developed proved successful, and its recipe remains unchanged to this day. Its popularity with the Royal Navy saw bottles of the product distributed all over the world.

In 1898 Gordon & Co. amalgamated with Charles Tanqueray & Co. to form Tanqueray Gordon & Co. All production moved to the Gordon's Goswell Road site. In 1899, Charles Gordon died, ending the family association with the business.

1793

Plymouth Gin

In the early nineteenth century Plymouth, London, Bristol, Warrington and Norwich were the great gin distilling centres each with their own unique gins. Gradually the London Dry style came to dominate but the gin made in Plymouth retained its own distinctively aromatic character. Plymouth Gin has remained true to this tradition. Produced in a still, which has not been changed for over 150 years, it has a subtle, full bodied flavour with no bitter botanicals.

Plymouth Gin has a long history. The Black Friars Distillery in Plymouth, where it is made, dates back to at least 1793 and there is reason to believe that distilling may have been carried out on these premises much earlier. Certainly Black Friars can rightly claim to be the oldest working distillery in the UK. The building is also reputed to have been the place where the Pilgrim Fathers gathered before they set off in the Mayflower for America in 1620.

Although Plymouth Gin is made in exactly the same way as London Gin, it is the only UK gin to have a geographic designation a bit like an appellation controllee – the result of a series of legal decisions in the 1880s when London distillers began producing a Plymouth gin. Coates & Co established then that, legally Plymouth Gin could only be made within Plymouth’s city walls.

One of the world’s great brands of gin, Plymouth Gin suffered years of neglect in the hands of the multinationals who often acquired Coates & Co as part of a job lot and never really appreciated the brand’s qualities and heritage. Plymouth is now happily ensconced in Chivas Brothers’ gin portfolio and is owned by giant Pernod Ricard.

1824

Pink Naval

Pink gin is widely thought to have been created by members of the Royal Navy. Plymouth gin is a 'sweet' gin, as opposed to London gin which is 'dry', and was added to Angostura bitters to make the consumption of Angostura bitters more enjoyable as they were used as a treatment for sea sickness in 1824 by Dr. Johann Gottlieb Benjamin Siegert.

The British Royal Navy then brought the idea for the drink to bars in England, where this method of serving was first noted on the mainland. By the 1870s, gin was becoming increasingly popular and many of the finer establishments in England were serving pink gins

1830

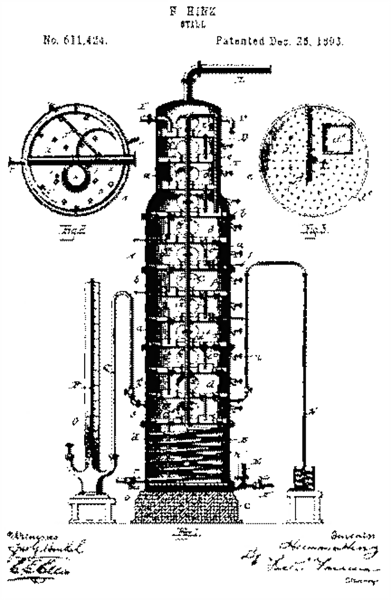

The Coffey Still

THE GIN ROAD TO REDEMPTION

In 1830, things finally started looking up for England’s gin scene. A French-born Irishman named Aeneas Coffey introduced a new still that modified the existing continuous column still and essentially revolutionized liquor production around the world. Gin producers quickly embraced it, celebrating its capability to produce a much cleaner, purer spirit than ever before. Out with the sawdust-infused gin, and in with the crystalline elixir.

Another category boost came courtesy of the British Royal Navy. England’s sailors often found themselves traveling to destinations where malaria was prevalent, so they brought quinine rations to help prevent and fight the disease. Quinine tasted notoriously awful, so Schweppes came out with an “Indian Tonic Water” to make it palatable.

London Dry gin accompanied the sailors on these voyages. It was in fashion at the time and made for better cargo than beer, as the latter quickly spoiled in the sweltering bellies of ships. So, like true Englishmen, eventually the two liquids were combined to form what is now the classic gin cocktails. Limes were added due to their anti-scurvy properties, thus birthing the term “limey,” a moniker for sailors.

Cordials were made to preserve the limes, and a lime cordial and gin were inevitably combined (hello, Gimlet).

1832

London Dry

Historically, the term “Dry Gin” came about with the advent of the Coffey still in 1832, long after the Gin Craze had driven London to distraction. Prior to this, gin had been made crudely – rudely, almost – and was of such a poor quality that it needed to be jazzed up with a hearty dose of botanicals with sweetening properties (like liquorice root) and sometimes even sugar or honey added post distillation to make it more palatable. Once the Coffey still came into action and a more consistent (and critically, more neutral) spirit was available, unsweetened gin started gaining popularity and became known as “Dry Gin”. As most dry gin producers were based in London, the products were sometimes referred to as “London Dry Gin.”

The flavour profile of London Dry Gin was more juniper-lead, with a touch of citrus and a rooty finish, and while many of today’s makers stay true to this (Tanqueray, Beefeater, Gordon’s, East London Liquor Company), there is a noticeable shift in taste lately, and there are many distilleries using the London Dry method to create completely untraditional tasting gins.

The first thing to note is that a London Dry Gin doesn’t have to be made in London; it doesn’t even have to be made in England. Instead, London Dry (also known as London Gin) refers to that which is made under a series of mind-bogglingly exciting EU regulations put in place in February 2008.

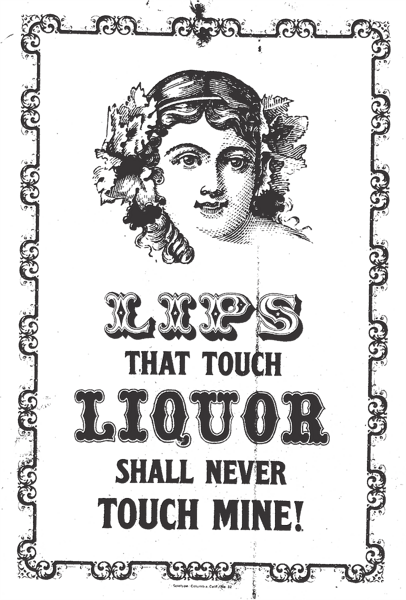

1919-1933

Prohibition

By the turn of the century, temperance societies were a common fixture in communities across the United States. Women played a strong role in the temperance movement, as alcohol was seen as a destructive force in families and marriages. In 1906, a new wave of attacks began on the sale of liquor, led by the Anti-Saloon League (established in 1893) and driven by a reaction to urban growth, as well as the rise of evangelical Protestantism and its view of saloon culture as corrupt and ungodly. In addition, many factory owners supported prohibition in their desire to prevent accidents and increase the efficiency of their workers in an era of increased industrial production and extended working hours.

Ratified on January 16, 1919, the 18th Amendment went into effect a year later, by which time no fewer than 33 states had already enacted their own prohibition legislation. In October 1919, Congress put forth the National Prohibition Act, which provided guidelines for the federal enforcement of Prohibition. Championed by Representative Andrew Volstead of Minnesota, the chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, the legislation was more commonly known as the Volstead Act.

Both federal and local government struggled to enforce Prohibition over the course of the 1920s. Enforcement was initially assigned to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), and was later transferred to the Justice Department and the Bureau of Prohibition, or Prohibition Bureau. In general, Prohibition was enforced much more strongly in areas where the population was sympathetic to the legislation–mainly rural areas and small towns–and much more loosely in urban areas. Despite very early signs of success, including a decline in arrests for drunkenness and a reported 30 percent drop in alcohol consumption, those who wanted to keep drinking found ever-more inventive ways to do it. The illegal manufacturing and sale of liquor (known as “bootlegging”) went on throughout the decade, along with the operation of “speakeasies” (stores or nightclubs selling alcohol), the smuggling of alcohol across state lines and the informal production of liquor (“moonshine” or “bathtub gin”) in private homes.

In addition, the Prohibition era encouraged the rise of criminal activity associated with bootlegging. The most notorious example was the Chicago gangster Al Capone, who earned a staggering $60 million annually from bootleg operations and speakeasies. Such illegal operations fueled a corresponding rise in gang violence, including the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre in Chicago in 1929, in which several men dressed as policemen (and believed to be have associated with Capone) shot and killed a group of men in an enemy gang.

In 1932, Franklin D. Roosevelt defeated the incumbent President Herbert Hoover, who once called Prohibition "the great social and economic experiment, noble in motive and far reaching in purpose." Some say FDR celebrated the repeal of Prohibition by enjoying a dirty martini, his preferred drink

1939-1945

Gin wins the war

the Plymouth Blitz of World War II. The German bombing raids may have completely destroyed Plymouth Gin’s offices and archives—you can still see a few charred beams in the Refectory Bar’s ceiling—but the distillery ultimately survived.

“The granddaughter of a World War II British Royal Navy sailor told us the story of how her grandfather had written in a letter that the bombing of Plymouth was the death knell for Hitler,” says Sean Harrison, the Master Distiller of Plymouth Gin, of a story a patron once told him at the bar. “This was because the thought that Plymouth Gin had been lost forever so incensed the men of the British Royal Navy that Hitler’s fate was sealed.”

2009

Ginaissance

Britain’s seemingly unquenchable thirst for gin saw consumers buy 66m bottles last year, a 41% annual rise, fuelling a spirit-making boom that has led to the number of distilleries in England overtaking Scotland for the first time.

The UK’s long hot summer provided the massive boost in sales, with more than 19 million more bottles sold than in 2017, taking total UK sales to £1.9bn.

The revival in the popularity of gin, or “ginaissance”, has broken Scotland’s centuries long domination of spirit making – built on the global popularity of scotch whisky. For the first time, more distilleries were operating in England than Scotland last year, 166 to 160, according to the Wine and Spirit Trade Association (WSTA).

“With England now boasting more distilleries than its Scottish cousins, 2018 really has marked a moment in history,” said Miles Beale, chief executive of the WSTA.

The latest figures from HMRC show that 54 new distilleries opened across the UK last year, with eight closures, taking the total in operation to 361. The number of distilleries in the UK has more than tripled since 2010, when the WSTA started keeping data and a year after the start of the renaissance of gin, when there were just 116.

England has led the boom in craft and premium distilleries, accounting for 39 of the 54 new operations started last year. There were 11 in Scotland and two each in Wales and Northern Ireland.

In 2010, England had just 23 distilleries, last year it hit 166, accounting for 58% of all UK openings in the last eight years.

Scotland is home to some of the largest distilleries in the UK, but an increasing number of smaller distilleries have emerged across the country, many of them diversifying and making new gins, whiskies, vodkas, rums, brandies and liqueurs.

Sign up to the daily Business Today email or follow Guardian Business on Twitter at @BusinessDesk

Last year, the drinks giant Diageo said gin was the fastest-growing category across western Europe, with sales up 22%. Its Gordon’s brand, the industry leader, launched a pink gin variant in summer 2017.

Flavoured gins have accelerated the gin boom that began in 2009 with the launch of the Sipsmith craft brand. Supermarkets have also cashed in with own-label craft sprits, while the discounters Aldi and Lidl have put out premium flavoured gins. In 2017, the number of trademarks registered for spirits and liqueurs in the UK leapt by 41% to 2,210.

Such is its popularity that in 2017 the Office for National Statistics added gin to the basket of goods it monitors to measure inflation